A place for memory

A roll of film lay unspooled at my feet, spiralling away like a loose curl. It was long exposed to the soft light that found its way in through dusty windows, fingers of eager plants stretching across their panes. The rest of the room was a mess of broken furniture, papers, rubbish and wires. On a table I found a photo of a young boy in soccer gear, smiling and giving a double victory sign, in front of a bunch of baby cacti. Who was this boy? Did he know his image permanently lived there?

That day we were at a former military neighbourhood in Taiwan where soldiers and their families once lived. The place looked like it was vacated in a hurry. As though the former inhabitants had no time to decide what was worth keeping and what could be left behind. In some houses it felt like the souls who lived in these homes just evaporated. Part of some exclusive rapture that left the rest of us behind.

And thus, remained this image, untethered from its story. Photos are visual signposts. A way to jog memory or conserve a moment forever in the present. They are things to be looked at and yet here was a personal keepsake lying perpetually unobserved, like some ancient artefact unearthed from the tomb of a nameless corpse.

Taiwan was full of these places. Factories, shopping malls, hospitals, amusement parks, half built villages, beach resorts dotted with space age UFO houses, breweries. All left to slowly fade, an unplanned but inevitable obsolescence. All it took to discover a new abandoned building was to jump on the back of my scooter and ride around seeking tell-tale signs. I started this weekly hunt in Changhua, the city where I first lived. The city lay in the shadow of Baguashan, and was surrounded by polluting factories. Their towering smoke stacks were painted in innocuous candy cane attire or bafflingly, with happy farm animals. Baguashan, a small mountain, was home to a massive seated Buddha. His calm gaze watched over the town’s inhabitants, busily working their way through the motions of the day. It was exploring this area that I came upon an old abandoned school, tucked away at the end of a winding mountain road.

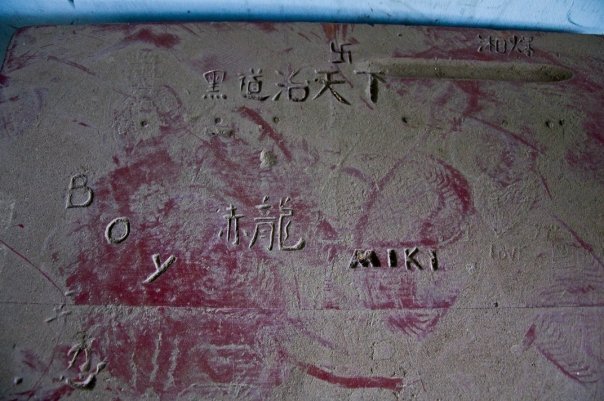

Multi-storied buildings surrounded a courtyard that was slowly being taken over by giant banyan trees, spider like limbs twisting through the overgrown grass. Blackboards caked in chalk dust still held the remains of lessons. The ordered shapes of the traditional Chinese characters still clung to their forms. Chairs were pushed neatly behind empty desks, ready for a class that would never come. The dust had embedded itself into the grooves of graffiti carved by bored hands. The shelves in the library had fallen into one another like lonely dominoes, spilling their books to the floor.

A darkened room revealed an eerie row of mannequin heads, unblinking eyes keeping watch. There were sinks for washing hair and old-fashioned tubular hair dryers. One of the heads had fallen to the ground and half imploded. The hair had come off in clumps. If it wasn’t made of plastic it would be as though I’d discovered a grisly murder scene. Later, I do come across a corpse. The body of a bird slowly decomposing. I can see the ribs that once encased its heart and the maggots that are feasting on its body. The skull of its head is delicate and beautiful. Mortality is a human preoccupation but I wanted to capture the existence of this bird before it completely disappeared. The picture I took that day hangs in the lounge of my house. My own morbid memorial to mortality.

When someone dies it is not uncommon for the loved ones left behind to cling to traces of the deceased. They keep their bedroom as it was when they died, or refuse to give away their clothes. They curl up within a piece of furniture that is infused with their smell. Shrines to the past, for those still not ready to let go. I had the strange feeling of being within a massive open air shrine when discovering the grounds of Nara Dreamland near Kyoto. We had travelled to Japan in the height of summer, and I found the shoebox rooms comforting respite from the heat. It had transpired that the hostel we had chosen was right next door to Nara Dreamland, an amusement park modelled on Disneyland that had never found its stride. Perhaps the lure of Tokyo Disney spelled its demise. We had been warned that it was heavily guarded by security but despite sneaking in through the back entrance we needn’t have worried. The place was a ghost town.

Empty cable cars hung in tidy rows, suspended just above the concrete floor. One had stopped at the apex of the semi-circular track above, unsure if it was coming or going. I was tense at first. We spoke only in whispers, setting up our tripods in silence, aware that our conversation could alert a passing guard. But our wariness gradually dissipated and was replaced with the giddy exhilaration of what we had discovered. Every ride was intact. The candy coloured coatings of the buildings still maintained their saccharine hue. We climbed reverently onto a towering wooden rollercoaster, that curved away into the distance before twisting back on itself. Each rise and fall of the track became less gentle, the gradient rising, the drop sharper. But without the essential element of a hurtling cart shooting screams into the air it was far more peaceful. The arcs of the track like undulating hills that filtered the morning light through their endless criss-cross of beams.

The Screwcoaster, deeper in the park, was an ode to a corkscrew. Its structure a metallic echo to unspooled film. It twisted away into the distance, into grass so high it obscured much of the track. Nature was beginning to reclaim the site, decolonisation of the earthly variety. You could feel the absence of the bodies profoundly. The rides were robbed of their purpose and their empty seats seemed lonely reminders of the park’s failure. In one corner of the park was a seated mannequin in a khaki jumpsuit. His entire face was gone leaving only a gaping hole. His identity had faded along with the rest of the park’s former staff. Nara Dreamland was destroyed not long after we visited. Maybe we were the last ones to see it before it was gone. Abandoned places are like snapshots fading away in an album. The timeline of these places has stopped but recording their image aids in their survival.

I become fascinated with what was left behind: glass jars containing fleshy shapes in an abandoned hospital; an old projector and film reel in the fetid depths of an amusement park; clothes hanging neatly on hangers in a dormitory; piles of cassette tapes, stickers faded beyond recognition and no way to play their recordings; a wooden recess built into the wall with the stencilled shape of various tools, highlighting their absence; the formal stares of a collection of passport photos. Ghostly imprints of the past. Taiwanese could be incredibly superstitious. They had an uncanny ability of knowing whether someone had died in one of the apartments in their building. Second hand shopping was only just gaining popularity; people were fearful of buying something that had once belonged to a dead person. An entire half-built village, damaged in the devastating 9/21 earthquake was believed to be cursed and no one wanted to buy the skeletal structures. I am not one to buy into stories of the supernatural but there was something undeniably eerie about these places. Full of the ghosts of the past, sometimes it felt like there was some lingering energy in the air.

In my early twenties I visited Auschwitz, an abandoned place now reclaimed. My trip to Poland had largely been an exercise in youthful hedonism with this visit the sobering counterpoint. Auschwitz lies on the outskirts of Krakow and has become a museum of lost objects. Forever severed from their original owners they now lie behind glass in darkened rooms gathering dust as endless streams of visitors shuffle past in hushed silence. There were hallways of hair and glasses and shoes and suitcases. Cracks had formed in the leather of the luggage, like neurons firing. A thick plait of blond hair secured with a ribbon stood out amongst a mountain of hair. Hair that had once belonged to a human, with an entire genealogy and history. The piles of hair stretched away into the darkness, the immensity heightened the absence. It was like looking into a void. The former gas chamber made my skin crawl. Perhaps it is the knowledge of what took place within these walls. But it’s as though the room has held tight to its history, walls rigid, the chimney an accusation, the floor tired but unwilling to forget. Structures are not simply backdrops to the people that inhabit them. The material world embeds itself within the physical space; it remembers. Places retain the memory of what took place within them.

The merging of tourism with sites that document disaster or past atrocities is part of what has been labelled as dark tourism. Spaces such as Auschwitz in Poland, Robben Island in South Africa or even the former site of the twin towers in New York City all fall under this rubric. Perhaps this is the travel sized version of rubber necking. Or maybe our desperate need to remember these moments, no matter how awful, so they don’t happen again. But humans seem slow learners when it comes to the lessons of history. Or maybe we are just telling the wrong stories.

In his seminal piece on the spaces of memorialisation or lieux de m moire, Pierre Nora describes memory as “a perpetually active phenomenon, a bond tying us to the eternal present; history is a representation of the past”1. The act of remembrance is not a passive event but is in constant flux. Memories interact and are constantly renegotiated and shaped through these interactions. Spaces that seek to commemorate or in some way archive historical events are curating the past. Memories imply a subjective experience and heritage conveys a sense of shared history therefore spaces that bring together shared memories of the past constantly reproduce and reshape heritage.

Memorials, such as Auschwitz, are viewed as places where collective memory is embodied within an object or space. Though people interact with these spaces the “memorial flattens the extremes of individual memory, replacing it and therefore, in a sense, denying it or suppressing it with something altogether more palatable, if not anodyne”2. Memorials can offer a particular narrative of events, shaping the way it is remembered and participating in selective amnesia. Memorials or museums that preserve dark aspects of the past, such as violent acts, war, disasters and mass death must navigate the tension between providing a record of what has occurred and engaging with collective memory, while not denying the individual experience of the event.

Creating specific spaces of memory can become a political act, encouraging selective remembering through erasure of particular unfavourable historical events. The politics of memorialisation are embodied in the selective remembering of two violent and disruptive events in the history of Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Aceh is a region that is still recovering from successive waves of thirty-year civil war, but it also was one of the worst regions to be hit by the 2006 Boxing Day tsunami. Both the tsunami and the conflict are embedded in the collective memory of Aceh. Objects and buildings that commemorate the tsunami have become sites of pilgrimage, such as the so-called ‘tsunami boats’ forced inland by the force of the waves and preserved in their final resting place. However, spaces that seek to remember the conflict, such as the Human Rights Museum, have fallen by the wayside.

Vigh3 highlights the normative dimensions of chronic crisis, the routinization of disorder that settles in when states of exception have become the norm. “Normal” may refer to the prevailing everyday violence—the things we do the most often, or that which there is most of around us. When the experience becomes a feature of the everyday landscape how do you extract memory from it? When the past holds such painful memories is it wrong to allow for a process of forgetting and progressing rather than maintaining its memory? I often think about the histories we never get to hear of. The history of the ordinary and mundane. Of women who were brilliant but unable to shine. I want to know the intimate details of their daily lives. Their routines. What they ate. What they thought about as they looked out at the world. I don’t want the stories of glory. I would rather know the quiet inner world of the everyday. I feel that reveals so much more about our history than the tiny snippets of time that have been documented. Recorded, official history is just like a photograph. It tells a story, offers some truth, but like an image it’s a construction. It doesn’t show what is lying out of sight just beyond the frame.

The places and objects we touch will often outlive us. As time stretches outward our existence remains fixed at the point of our demise. But the mise-en-scene to our lives will hold the traces of us, memory merging with the material. Our history held in slowly fading structures, like a discarded negative exposed to the light.

(Part of this piece comes from a book chapter A Tale of Two Museums in Post-tsunami and Post-conflict Aceh, Indonesia, co-written with Dr Jesse Hession Grayman based on his doctoral research).

1 Nora, P. (1989). Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de M moire. P.8.

2 Simpson, E. and de Alwis, M. (2008). Remembering Natural Disaster: Politics and Culture of Memorials in

Gujarat and Sri Lanka. P.7.

3 Vigh, H. (2008). Crisis and Chronicity: Anthropological Perspectives on Continuous Conflict and Decline.